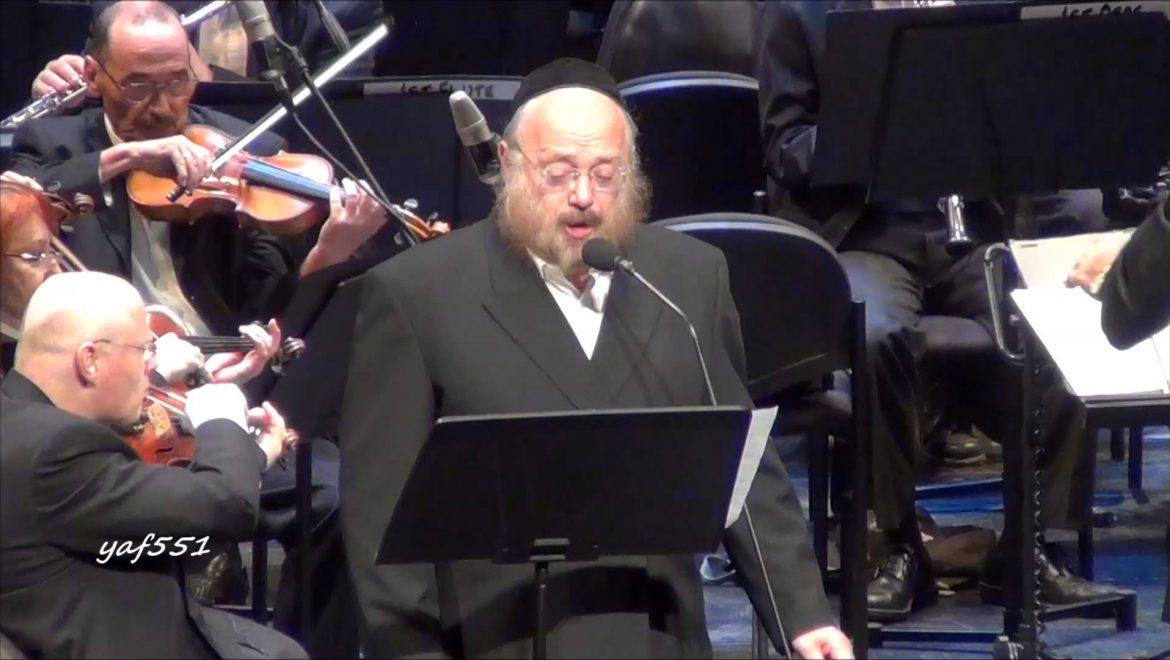

This post includes an article from The New York Times about the Jewish composer, Ben Zion Shenker, who composed the most famous melody for Eishet Chayil, sung in Jewish homes around the world each week. The accompanying video features a performance of this well known melody from a concert dedicated to the greatest Jewish composers. This rendition is performed by the Raanana Symphonette Orchestra and the Rinat Yisrael Choir.

Ben Zion Shenker, Rabbi Who Wrote Prayer Melodies, Dies at 91

Rabbi Ben Zion Shenker, regarded as perhaps the leading composer of Hasidic prayer melodies, whose music flavored the religious life of Orthodox Jews and influenced popular klezmer bands, died on Sunday in Brooklyn. He was 91.

His death was confirmed by Sruly Fischer, the husband of one of his granddaughters, who said Rabbi Shenker had a heart ailment.

Rabbi Shenker was the foremost composer and singer of the Modzitzer Hasidim, a Polish-rooted Hasidic sect that is known for melodies composed for the texts of Sabbath and holiday prayers, and for humming at moments of spiritual expression.

For the Modzitzer, as for all Hasidim, music and dance are vehicles to bring Jews closer to God, in accord with a philosophy expounded in the 18th century by the founder of Hasidism, the Baal Shem Tov.

Rabbi Shenker composed more than 500 melodies, and they have been recorded not only by him, but also by other musicians, including the violinist Itzhak Perlman; Andy Statman, the klezmer clarinetist and bluegrass mandolinist; and the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.

He also influenced the music of Shlomo Carlebach, regarded by many as the foremost songwriter of Jewish religious music and a leading figure in the movement to bring secular Jews back to religious observance.

Rabbi Shenker’s most widely heard compositions are the melodies for “Eshes Hayil” (“Woman of Valor”), sung at dinner tables after sundown to welcome the arrival of the Sabbath, and for the 23rd Psalm, “Mizmor L’David” (“A Psalm of David”), sung at the last meal of the Sabbath. His “Yasis Alayich” (“Rejoice Over Thee”) is played at most Hasidic weddings.

“After the Hasidim fled Europe, he became the repository of all that music,” said Mr. Statman, who was working with Rabbi Shenker on a recording just days before his death. “He was a supremely musical person, and his understanding of how to sing a melody, color it and ornament it was just incredible.”

Rabbi Shenker was born on May 12, 1925, in Brooklyn, four years after his Hasidic parents, Mordechai and Miriam Shenker, emigrated from Poland.

From childhood, he was enchanted by the singing of cantors like the great Yossele Rosenblatt, whom he heard on his parents’ phonograph. At 12 he joined a choir conducted by a prominent cantor, Joshua Samuel Weisser, who featured him as a soloist on a Yiddish-language radio program.

He began studying composition and music theory at 14, but his musical path was determined shortly after that, when he encountered Rabbi Shaul Yedidya Elazar Taub, the rebbe, or chief rabbi, of the Hasidim whose roots were in Modrzyce (Modzitz in Yiddish), a borough in the town of Deblin, near Lublin, Poland.

Rabbi Taub had escaped from Nazi-occupied Poland and made his way to Brooklyn in 1940 by way of Lithuania and Japan. Virtually every chief rabbi in the Modzitz dynastic line composed music, and Rabbi Taub was said to have written a thousand religious melodies.

On a visit to his house, the young Rabbi Shenker picked up a book of sheet music containing some of his compositions and quietly hummed the melodies. Since few Hasidim were trained musicians, the surprised rebbe asked, “You can read notes?” When Rabbi Shenker said he could, the rebbe asked him to sing the melodies out loud and was so taken with his talents that he asked him to be his musical secretary.

“Anything he composed, I used to notate,” Rabbi Shenker said in an interview on NPR in 2013. “And he used to sing for me things that he had in mind.”

Soon he was composing his own melodies and, with his reedy tenor, singing songs beloved by the sect for their tenderness, gracefulness and fervor. In 1956, he established his own label, Neginah, to record his first album of Modzitz melodies. He was backed on it by the all-male Modzitzer Choral Ensemble in a program of music composed for the post-Sabbath meal known as Melave Malke.

It was one of the first collections of religious melodies by an ultra-Orthodox musician, and it prompted other Hasidic dynasties to record their own melodies.

He eventually produced nine more records of Modzitzer music, including his own compositions. Since klezmer music, as Mr. Statman explained, is “really Hasidic vocal music played instrumentally,” Rabbi Shenker’s tunes also influenced klezmer performers.

Rabbi Shenker sometimes conceived his melodies sitting at a piano with a prayer book in front of him, sometimes while reading a religious text on the subway. But he earned most of his living in business, first in a family-owned sweater company and more recently as a partner in a small diamond business on West 47th Street in Manhattan.

His wife, the former Dina Lustig, died three years ago. He lived in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. Survivors include his daughters, Esther Reifman, Adele Newmark and Broche Weinberger; a brother, Rabbi Chaim Boruch Shenker; 23 grandchildren; and more than 90 great-grandchildren.

Anyone who wanted to sample Rabbi Shenker’s works could go to the Modzitzer synagogue in Midwood. For more than five decades he led prayers there, including those that were shaped by his melodies. And when he walked home on a Friday evening after services, he could hear his melody for “Woman of Valor” sung in almost every Jewish home in his neighborhood.

He said in the NPR interview that he had composed seven new songs for the prayers of that year’s Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur services.

“When those prayers come up, I’m the one that starts it, and the singing adds so much to the spirit of the prayers,” he said. “ I mean, when you sing it, you really understand it.”